I haven't, as they say, read the book but I have read the article. The book - Forgetfulness: Making the Modern Culture of Amnesia by Francis O’Gorman - is concerned with what is described as the 'systematic devaluation' of the past since the 19th century. As I understand it the basic points are that:

- societies are increasingly obsessed by the future and as such want to relegate where they came from in order to create the new order that will be so much better

- big organising ideas like communism found it necessary to sweep away everything that went before

- liberal societies are increasingly critical of their pasts and wish to denigrate them for failing to live up to modern ideals.

To say that this left me mildly puzzled is something of an understatement.

Listening to our current political discourse one could be forgiven for thinking that the past is in fact the major obsession of many of our politicians constituted as a weird amalgam of Our Island Story, The Second World War and Britain as viewed (by many of those very politicians) through sepia tints from parts of the world that had in the not too distant past been British colonies.

Indeed, it seems that our future is increasingly affected by deliberately distorted notions of the past which people across the globe are eager to use to justify all kinds of disastrous policies. That nice Mr Putin is very much the Imperialist and a latter day Peter the Great. The tragic state of the USA arises from completely separate narratives about the past and the foundation myths of the country and a systematic failure to reach any kind of common ground on the history of slavery and discrimination. The horrific events in the Middle East reflect an active ambition to go back to an imagined medieval past and to destroy all other cultures in the process.

The point about all of this is the not forgetting but the complete exclusivity of the views being propounded.

The past is not being used to draw some carefully calibrated lessons about what can happen and to aid understanding and reflection.

It is being used for malign purposes. It seems to me that we do not have a problem with amnesia. Far from it. We have a problem with spending far too much time on partisan commemoration but far too little time on reflection.

The commemorating focus is on 'heritage' (which is now often coupled with the word 'industry'). And one of the things about heritage is that it is deeply cultural and is associated with an expectation that it be viewed positively. It is in short reinforcing some of the story that we tell ourselves. It is about identity.

This commemoration obsession can seem mildly quaint or more than a touch ridiculous when seen in the obsessions of many British people with a past that is characterised by big houses, latter day indentured retainers and a class ridden stratified society represented in frankly repulsive programmes like Downton Abbey. This is indeed the Our Island Story version of history and it is more than just quaint or ridiculous when it becomes part of a wider narrative about our Imperial past as somehow a good thing rather than a disastrous exercise in expropriation and domination.

I spend more time than I should wandering around houses that were built by people who I would have found completely abhorrent. The past is fascinating but it needs to be viewed in a clear sighted manner. I want to understand but I have no interest in celebrating aristos and swaggering roaring boys.

So whenever I hear some nonsense about The War and how we were a top nation and how much better it would be if we were to let the lion roar again, my immediate reaction is to suggest that people should take a deep breath, have a cup of tea and spend some time reading the magisterial book The Uses And Abuses Of History by Margaret Macmillan. As she says:

'History is not a dead subject. It does not lie there safely in the past for us to look at when the mood takes us. History can be helpful; it can also be very dangerous. It is wiser to think of history not a a pile of dead leaves or a collection of dusty artefacts but as a pool, sometimes benign, sometimes sulphurous, that lies under the present, silently shaping our institutions, our ways of thought, our likes and dislikes.'

Using history as a basis for identity is a manifestation of history at its most sulphurous. Much of our history is not one of which we should be particularly proud. It is, however, what made us what we are today for good and ill. We should remember it but we should not commemorate; we should reflect and understand and be clear eyed in doing so. Above all we should see history and the study of the past as one of the great liberal disciplines and a bed rock of pluralism.

The danger it seems to me is from obsessives who choose a narrative grounded in the past to posit a purportedly better future. That these are frequently extreme nationalists or religious fanatics should come as no surprise.

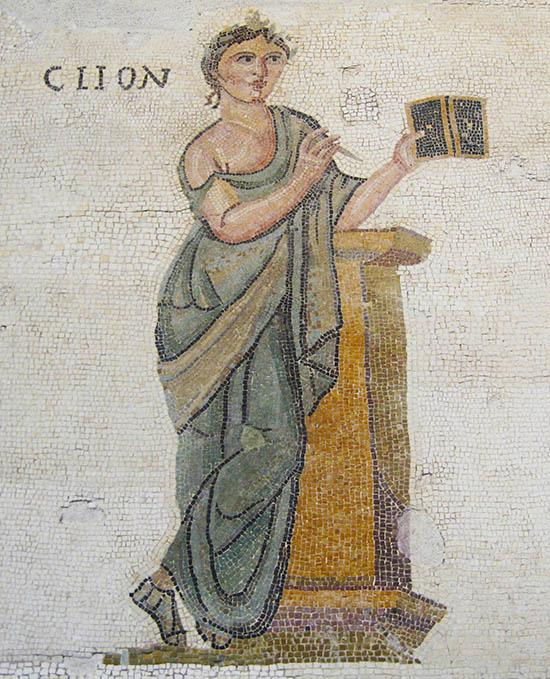

At this Clio, the muse of history (you can see her at the top of this blog), would weep copiously (and that's not just from the sulphur).

Yet we know that there are still exercises in enforced amnesia which continue and in these cases remembering what others have tried to eradicate is a wholly laudable enterprise. And when that is done with the kind of grace and intelligence that is on offer in this film Spell Reel about remembering the recent past in Guinea-Bissau one can see the power in doing so.

Remembering what others want forgotten is after all fundamentally about pluralism.

Comments

Post a Comment